Blog

Emily Humphreys is the the Eli Kirk Price Plant Science Fellow.

In September of 1994, a party of botanists from across the U.S. and China traversed a set of steep cliffs searching for

lacebark pine (Pinus bungeana). While the botanists found several trees, they all grew on slopes too steep and treacherous to navigate. Finally, Dr. Riming Hao of Nanjing Botanic Garden, in a great show of bravery, climbed one of the trees that stretched over the cliffside, collecting seeds and a cutting that were brought back to the Morris Arboretum. Today, that cutting resides in the Arboretum’s Herbarium.*

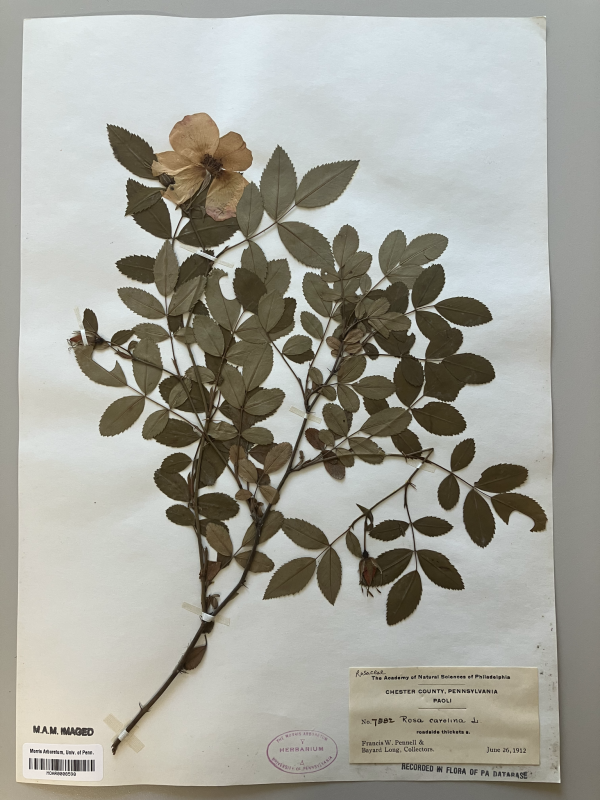

An herbarium is a lot like a library, except instead of books it holds botanical specimens. Each specimen features a pressed and dried plant, which can include anything from a tiny flower, roots and all, to a dense tuft of moss, to a cutting of a tree branch like the one Dr. Hao collected. This plant is glued on a special piece of herbarium paper. While the glue and paper are specially formulated to preserve the plants, the general process of mounting a specimen is not too different from a craft project. In addition to the plant itself, the specimen also carries information about that plant in the form of a label. The information on these labels varies widely, but most feature an identification for the plant, the location and date it was collected, and the name of the collector. Finally, some specimens have a little folded packet that is meant to hold any bits or pieces that fall off of the dried plant in its long tenure as a scientific asset.

With collecting, drying, mounting, preserving, and curating, maintaining an herbarium is a resource-intensive process. Over the years, many institutions have noticed the amount of work it takes and wondered: why go to all the trouble? Still, though it may not seem intuitive, herbaria are the foundation of much of what we know about plants today.

For centuries, herbaria have allowed scientists to see plants they would never have access to otherwise. Many new species have been described because experts noticed specimens that didn’t match any previously documented plant. Having specimens with associated locations allows scientists to compare plants across regions, and having specimens with associated dates allows them to compare plants across centuries and seasons. With all this data, researchers are asking complicated questions: As the Earth warms with climate change, have plants started flowering earlier? How closely related are different populations of the same species? Do specimens with more defensive chemicals have less insect damage?

Technological breakthroughs have amplified the power of herbaria. Many, including the Herbarium at the Arboretum, have specimens that are centuries old. When people were collecting many of these specimens, the structure of DNA was still unknown. Today, herbarium specimens are a widely used source of DNA for sequencing, allowing researchers to better understand plant evolution. This history begs the question: what information do these specimens contain that we can’t even begin to fathom today?

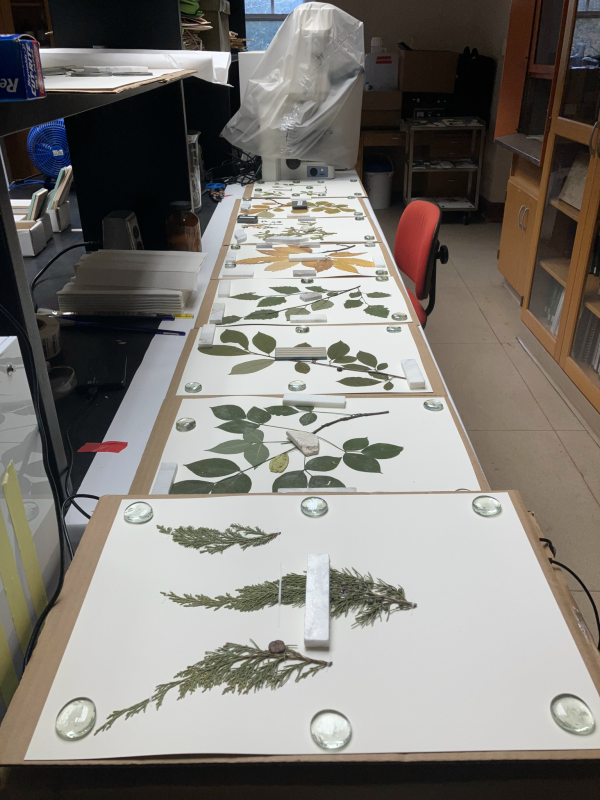

Technology has also allowed specimen data to be accessed far more easily than ever before. Across the world, efforts are underway to digitize herbarium specimens. Digitization typically involves taking a high-resolution image of the specimen and transcribing all the information on the specimen's label. In the past, if a researcher was interested in viewing a specimen, they would either have had to travel to the herbarium where it was housed or have the specimen shipped to them on loan. Now researchers can go online, search for specimens across herbaria, and download images and data in seconds. This has allowed for comparative research across the tree of life on a scale that was never possible before.

In a bright room in the attic of the Widener Visitor Center lives the Arboretum’s Herbarium. The collection contains more than 25,000 specimens, all of which have been digitized. From pressed orchids to parasitic mistletoe to oak branches with acorns, the Herbarium hosts a varied array of plants.

Some of these specimens were brought back from collecting trips like the one to China in 1994. Morris botanists and horticulturalists would join with professionals from other institutions and wild-collect interesting plants to add to the Arboretum. In addition to seeds for propagation, they would collect specimens to dry and add to the Herbarium. Because of this history, many of the plants thriving in the Arboretum today have corresponding wild-collected specimens in the Herbarium.

In addition to plants from around the globe, the Arboretum’s Herbarium has particularly strong representation of the Pennsylvanian flora. Many Morris botanists, including the current John J. Willaman Director of Plant Science, Dr. Tim Block, have specialized in studying and collecting our state flora. That legacy is evident today; roughly 78% of the Herbarium’s specimens were collected in Pennsylvania.

The Herbarium is open to visit by appointment and serves as an active research collection, sending out loans and welcoming researchers who come to look at specimens. Still, this isn’t the only way that specimens can be accessed. Thanks to digitization efforts, online versions of our Herbarium specimens can be found here. Next time you come to the Arboretum, try searching for some of the species you see. You might just stumble across the story of a dedicated botanist who went out on a limb to collect seeds from a pine tree.

*Thank you to Dr. Lulu Korsak for uncovering the story of the Pinus bungeana specimen.